The possible consequences of swallowing a soul… Wuthering Heights In a Cup of Tea? JA. 4/5/17

Above our farm (Whitestone Arts Research Centre) signposts on Haworth Moor are in English and Japanese…..

Like the hapless main character in Koizumi Yakumo (Lafcadio Hearn)’s translated story fragment In a Cup of Tea, (adapted for the 1965 Kwaidan film by Masaki Kobayashi), dreaming Lockwood swallows a soul right at the beginning of Emily Brontë’s stand-alone novel of unique genius, Wuthering Heights.

I’ve long wanted to find a way in to Lockwood’s extra-ordinary journey through the book and make it the main focus for a reinterpretation. I’ve dreamed (since I first came to live near Haworth Moor in the 1980s) of making a cross-art form exploration of Wuthering Heights that escapes the dominant and actually non-existent romantic/sexual relationship of its other two main protagonists much favoured by dramatists and readers alike.

Japan’s ghost tradition, physical performance and calligraphy traditions and Shinto instincts for the sanctity of landscape have unexpectedly revealed themselves as my beautifully adorned Torii (鳥居, literally ‘bird abodes’) into the novel: gateways for flights into unknown space.

The book will always evade every individual reading. Emily herself, maker of the text that carves the grass and flesh, brook, stone and narratives for us to tread among, remains dumb as the wind; yet she wrote it for our exploration, perhaps even for her own. As we journey around her imaginary landscape built from supple and operatic language, our compass needle will point, always, to Cathy’s ghost. She speaks of, and shows us, things other than the visible or readable, other than the actions described by all the other narrators, and it is poor Lockwood alone who has seen her – touched her – swallowed her. He’s haunted right from the start, like the victim of a vampire, and has become, for me, our true, though unwitting, guide out of cultural ignorance into a glimpse of Emily’s private and primal universe. In much the same way Lafcadio Hearn, splitting himself in two to become half Japanese by deliberately swallowing the soul of another culture, is our best, though imperfect, guide to the ghost world of early Japan (with much help from his Japanese wife’s acting out).

Wuthering Heights is not a book about “true romance” or unrealistic expectations or the need to grow up, choose and choose ‘wisely”. Nor is it a fantastical escape into gothic indulgence. It is a uniquely heretical book about identity, a woman’s identity, riven in two by loss and contradiction and a sense of the birth of her artistic genius being disallowed and invalidated by religion, society and culture because she is “other”. Female. Not in god’s image like Adam, yet “childishly” playing god when women should always be ghosts in the shadows: even – or especially – ghosts in their own houses. Home is where woman hides and bleeds and the homely becomes a thing of male terror. As Tanizaki points out, nervously: “our ancestors made of women an object inseparable from darkness” (In Praise of Shadows).

In that matter at least, East and West share very common ground, to the great detriment of a woman’s right not just for equality, but for existence itself in a world designed by a male god and his lookalikes.

Emotional tsunamis, earthquakes and terrible wars beat across Emily’s fictional moors, as actual terrors have torn and beaten Japan. Like dark matter from black holes or rent volcanoes, the landscape seems to emerge out of the fissures of this human strife in speeded astronomical / geological time. The identities of the characters, split between conscious and unconscious, birth ghostly selves to people it. The dead walk, most of them lost women and children, as the ghosts of Japan do, among the living: in broad daylight and outside our dreams. There is a unique nesting circularity (‘bird abodes’?) about the narratives in Wuthering Heights, circles within circles making a precise galaxy of its own. Cathy and her ghostchild alone take us on a quantum journey, reaching through this spacetime and across matter (like the spooky action at a distance of quantum particles) so the narrative collapses through itself, like a dying star.

(Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris has the same ideas of human actions and dreams as sources both of narrative and fleshly matter. That book, too, seems cursed with a romantic reading – see notes below).

Emily Brontë lives still in her haunted house. Two haunted houses, if we listen to her great admirer and namesake, Emily Dickinson: “One need not be a chamber to be haunted,/One need not be a house;/The brain has corridors surpassing/Material place”.

Wuthering Heights is a book about freedom from prison – the Palaces of Instruction – release not only from the tyranny of male culture, but from fecund nature too. It may well be a book, ironically, about not writing a book at all, about staying alive only if freedom to be true to one’s self, and one’s other self – to be and not do – is bestowed. Otherwise, better to die. One critic has suggested it is Emily Bronte’s suicide note. That can’t be biographically proved, but the narrative does have the detached imperiousness of a wrathful deity, a Child Genii who observes all, aloof. It is also propelled (literally) and self-haunted by the buried rage and grief of that same child abandoned, looking on, helpless; a child who is angry, and terrified of that anger: what it might be capable of, when the lost, dearest embrace can never return to hold her, and she, like all of us in the end “lies alone”.

The book is a unique alchemical collision of life and death in a crucible of ruthless energy. I would say passion, but the word’s been degraded to mean childish temper, sexual love (something Cathy herself would in the end identify as “sickly”) or religious fanaticism (something even Nelly ruffles her feathers over). Sex (loving or not), like war and religion, is a serial killer of women in the book, and in Emily’s world and in our world, still.

To explore this, I have decided that the islanded world of Wuthering Heights has a twin in that Gondal for “Grown-ups”, an archipelago that Childe Emily spookily locates in the North Pacific: In Ghostly Japan.

We are making a piece about the northern hemisphere’s twinned cultures, twinned houses and twinned psyches (one ‘real’, one ‘imaginary’). Childe Lockwood (the only other character in the book, apart from Heathcliff, with a single name), like Childe Hearn, is put out upon the moor to live or die in a culture wholly “other”. We journey with them. Surely they, not Cathy and Heathcliff, are our alter egos.

East and West – separate or together? – forever divided or uncanny attendant ghosts to each others’ identities?

Time to clutch our compasses and walk ‘where our own natures would be leading’. Both here – and there.

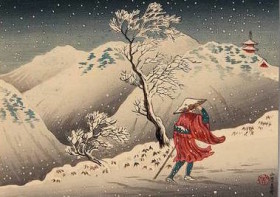

Traveller in the Snow by Takahashi Hiroaki

Notes:

Victoria Nelson: The Secret Life of Puppets:

...the classic post-Colonialist argument: if the western imagination does no more than project its own psychic Terra Incognita onto the rest of the Earth, then we correctly regard such accounts of these regions as portraits of an alter ego, not an alter orbis. The colonialist’s psycho-topographic presumption is to seek the Other and find only his own reflection. Solaris presents the exquisite joke that, for once, rejected contents of the psyche are projected onto an Other who is having none of it and – to the total psychological undoing of the projectors – reflects these contents right back to them….Solaris is found to contain, Chinese-box like, its own alter orbis………the two polar fundamental principles of the universe are form as the light principle, coming from above, and matter as the dark principle, dwelling on earth…In the middle, the sphere of the sun, where these opposing principles just counterbalance each other, there is engendered in the mystery of the chymic wedding, the infans Solaris, which is at the same time Great Child and the liberated world-soul.”

Lafcadio Hearn (Koizumi Yakumo): In Yokohama, Out of the East:

I began to think the unthinkable. That the ghost in each one of us must have passed through the burning of a million suns, must survive the awful vanishing of countless future universes. Eternally the swarms of suns and worlds are born; eternally they die. And after each tremendous integration the flaming spheres cool down and ripen into life; life ripens into thought. May not Memory somehow, somewhere, also survive? As infinite vision. Remembrance of the future in the past. Dreams of all that has been and can ever be are being perpetually dreamed.

Cathy Earnshaw, Wuthering Heights pg 79

“I’ve dreamt in my life dreams that have stayed with me ever after, and changed my ideas; they’ve gone through and through me like wine through water, and altered the colour of my mind.”